Cover image by Artem Bryzgalov

Do Androids Dream of Original Ideas

The following is a slightly modified transcript of a talk I did a couple of months ago.

Today, I aim to answer one simple question: Do androids dream of original ideas? To answer this question, we’ll go back to last week, when I was desperately trying to put together a talk about AI and creativity.

I asked an AI to create a painting of a sunset over a cyberpunk city. In seconds, it gave me something beautiful. I like it, but I also feel disconnected from it. I felt there was something missing—some spark, some soul, some evidence of a mind that had actually watched the sun sink behind the forest of glass and metal and felt something about it.

It was a sunset that conscious eyes had never witnessed. A city generated by averaging millions of city photos from around the world. Maybe it’s common to feel that about artistic work by others, but it’s very strange when it’s supposedly my own.

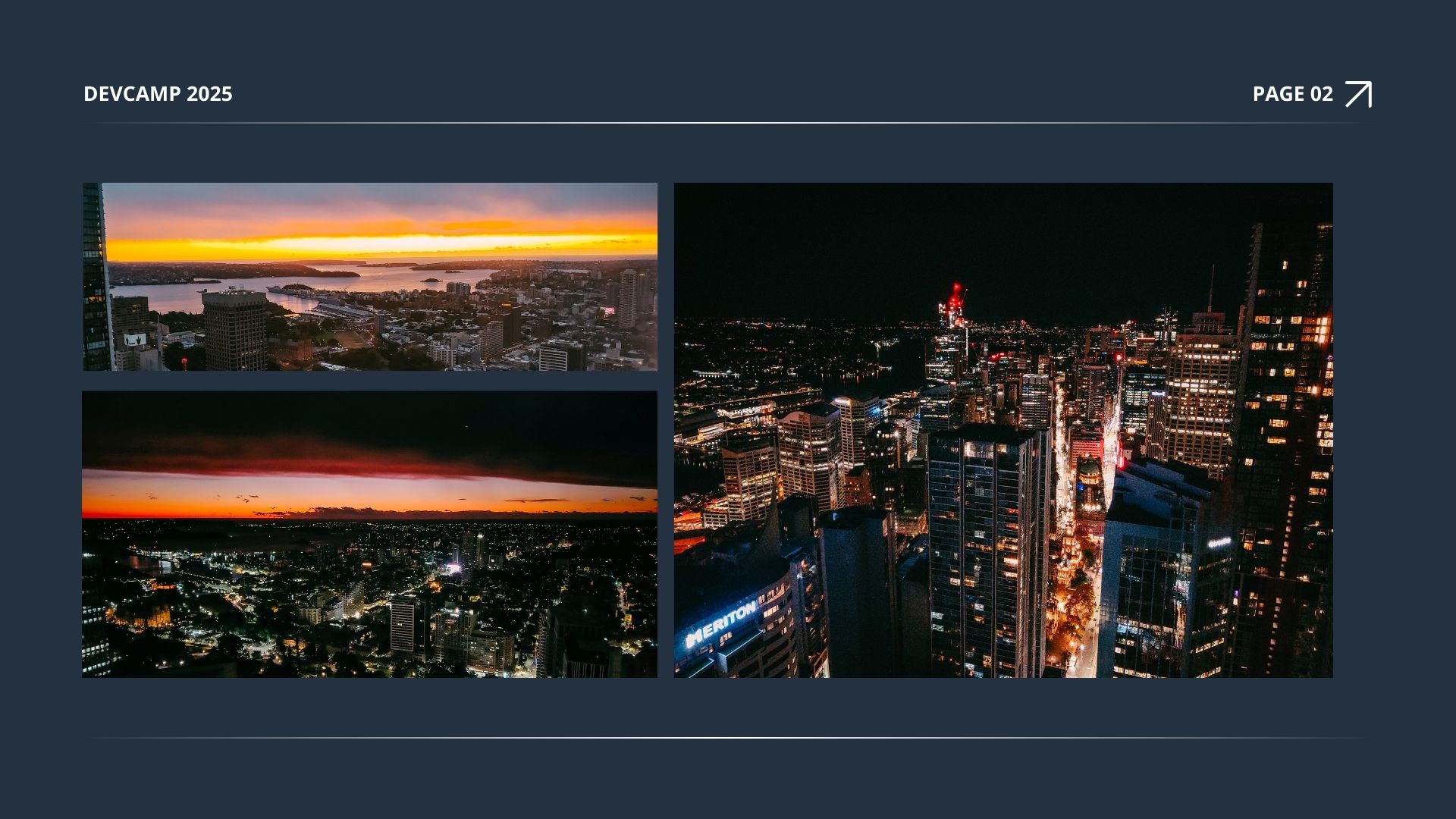

After creating this AI art, I dug through my photos and found these to compare. These are some of my photos of Sydney City at night and the creeping sunrise following. I noticed something when looking at the city in them: it’s not as homogenous as an AI city. In an AI city, every building appears to be designed and constructed within the same era.

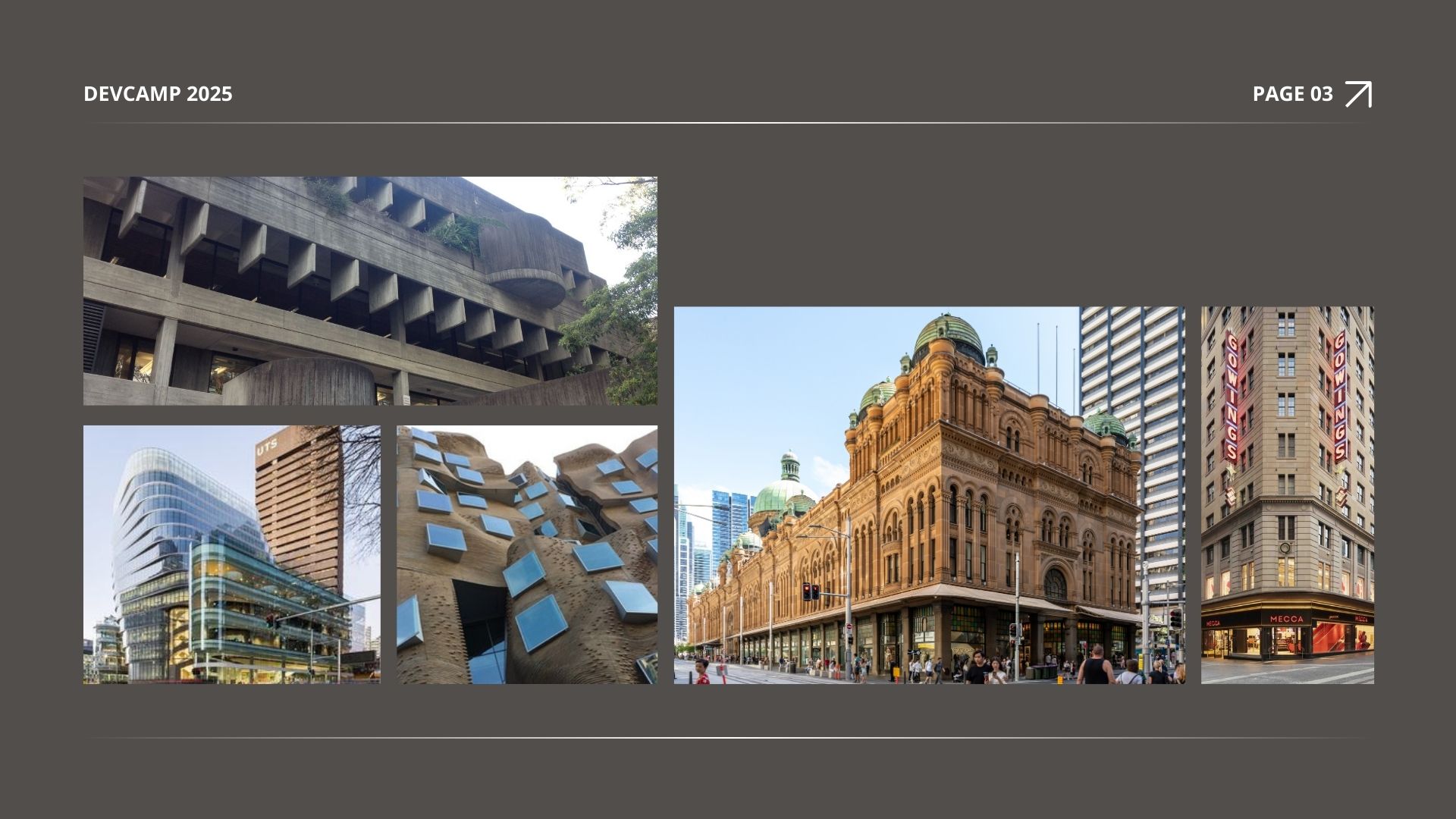

We aren’t going to get a brutalist high-rise building next to a contemporary glass building with a deconstructivist building in the background. Or a Romanesque revival hall with a commercial Palazzo-style building in the background unless we specifically ask for it. But we do get this in real life—just head back up to Sydney, and you’ll see these buildings.

This was it. This was the spark that got me going.

So here’s the thing: We’re living through a creative revolution—or at least, that’s what we’re told. AI systems now generate content faster and cheaper than we could; all users have to do is articulate what they want into words.

These AI systems write essays and poems, compose songs, create illustrations and animations, and even code software. The barriers to creation have never been lower.

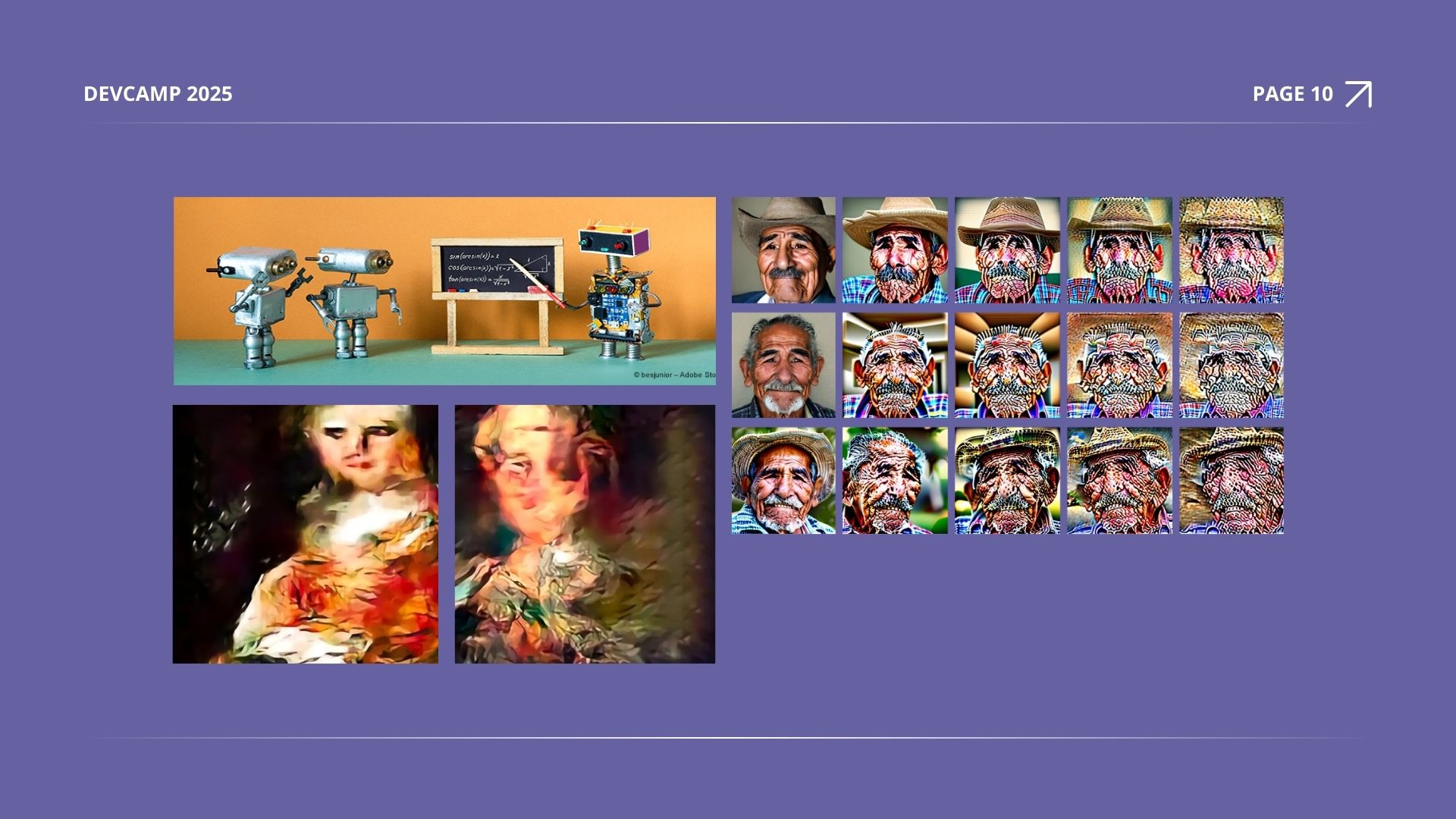

These AI systems don’t create in the human sense. They analyse vast datasets of human-created work, identifying patterns and statistical relationships within that data.

Consider how an AI writes a story about love. It doesn’t draw from personal experience of heartbreak or connection. It averages millions of existing human stories about love, finding patterns in plot structures, character dynamics, and emotional arcs and recombining them.

As AI content proliferates, it homogenises. When trying to be creative, AI systems pull toward the centre of their training data—toward what’s already been done, what’s statistically common, and what’s “safe.” The result is a growing sea of content that feels strangely familiar yet empty, like songs you’ve heard before but can’t quite place.

After all, consider the source material the AI is drawing from. It’s similar to piracy websites. The more specialised or niche the content, the lower the likelihood of its presence on the platform. However, considering the massive popularity of Marvel movies and New York Times bestsellers—it’s not surprising that there are hundreds of different copies of those available online.

But a broader cultural trend is at play here, one that predates AI but now mixes with it in dangerous ways. Across architecture, design, music, fashion, marketing, we’re witnessing a flattening of aesthetics. You can book an Airbnb in Tokyo, London, or Barcelona and find yourself in an apartment with the same elements: white walls, mid-century chairs, Edison bulbs, bare wood, and maybe a fiddle-leaf fig in the corner.

This is caused by the globalisation of taste, the dominance of data in decision-making, and the risk aversion of corporations trying to appeal to the widest possible audience. We have been converging toward a safe, familiar middle, same as AI. It’s technically competent and aesthetically inoffensive, just like AI content.

AI didn’t cause this—but it will accelerate it. It’s trained on the same average content that’s already everywhere and generates more of it. AI doesn’t know how to be weird unless we prompt it to be, and even then, it’s weird in a predictable way.

Nevertheless, with AI, this homogeneity creates its own problem, as we see with the phenomenon of model decay, which happens in two main ways:

First, the real world keeps changing while the AI’s training stays frozen in time, like using an old map in a rapidly developing city.

Second, as AI-generated content floods the internet, future AI models increasingly train on synthetic data rather than authentic human content, creating a feedback loop where each generation becomes progressively worse at understanding genuine human communication.

This creates a double problem—models become both outdated and less human-like over time.

When we create something—whether a story, a painting, or a piece of music—we’re drawing from a well of lived experience that AI simply doesn’t have. Every piece of art that moves us does so because another human being transformed their experience into something tangible.

Our subconscious minds are deeply aware of not only this specific context but also the crucial significance of context in general, understanding its impact on our perceptions and interpretations. When my grandfather-in-law moved across the world, he picked up woodcarving and incorporated his cultural context into his work. Here, his first carving and his last show that it wasn’t technical lifelike perfection that granted his acclaim, but the heart put into the work.

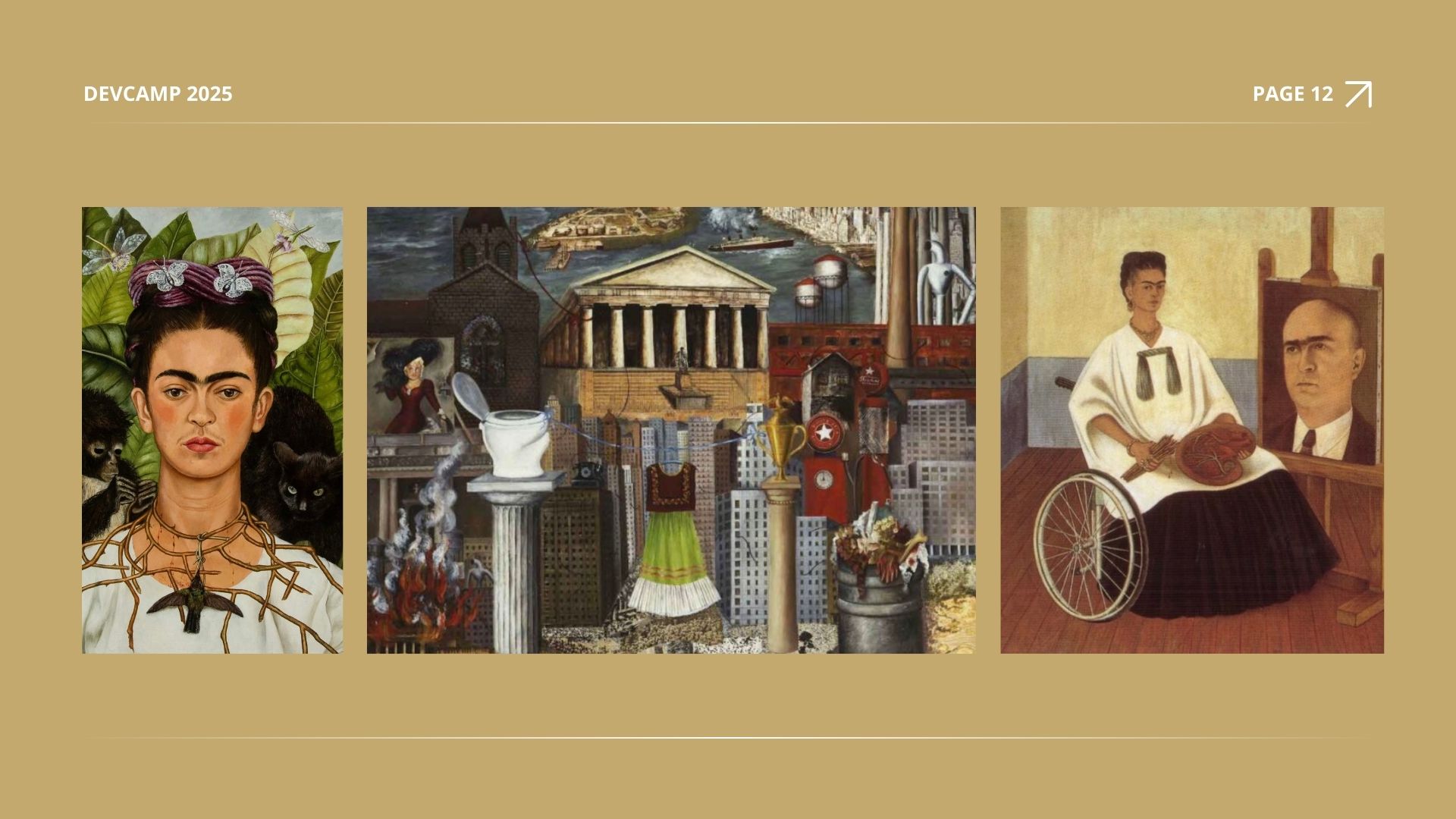

Similarly, consider Frida Kahlo’s self-portraits—works that transcend technical mastery because they are physical manifestos of her existence. Born from spinal trauma, miscarriages, and her identity as a Mexican woman navigating post-colonial gender norms, her canvases pulse with vulnerability. When Kahlo paints her body split open to reveal a broken column, we witness the transformation of agony into art; we appreciate the vulnerability and the strength it took to create something so personal, painstakingly, by hand.

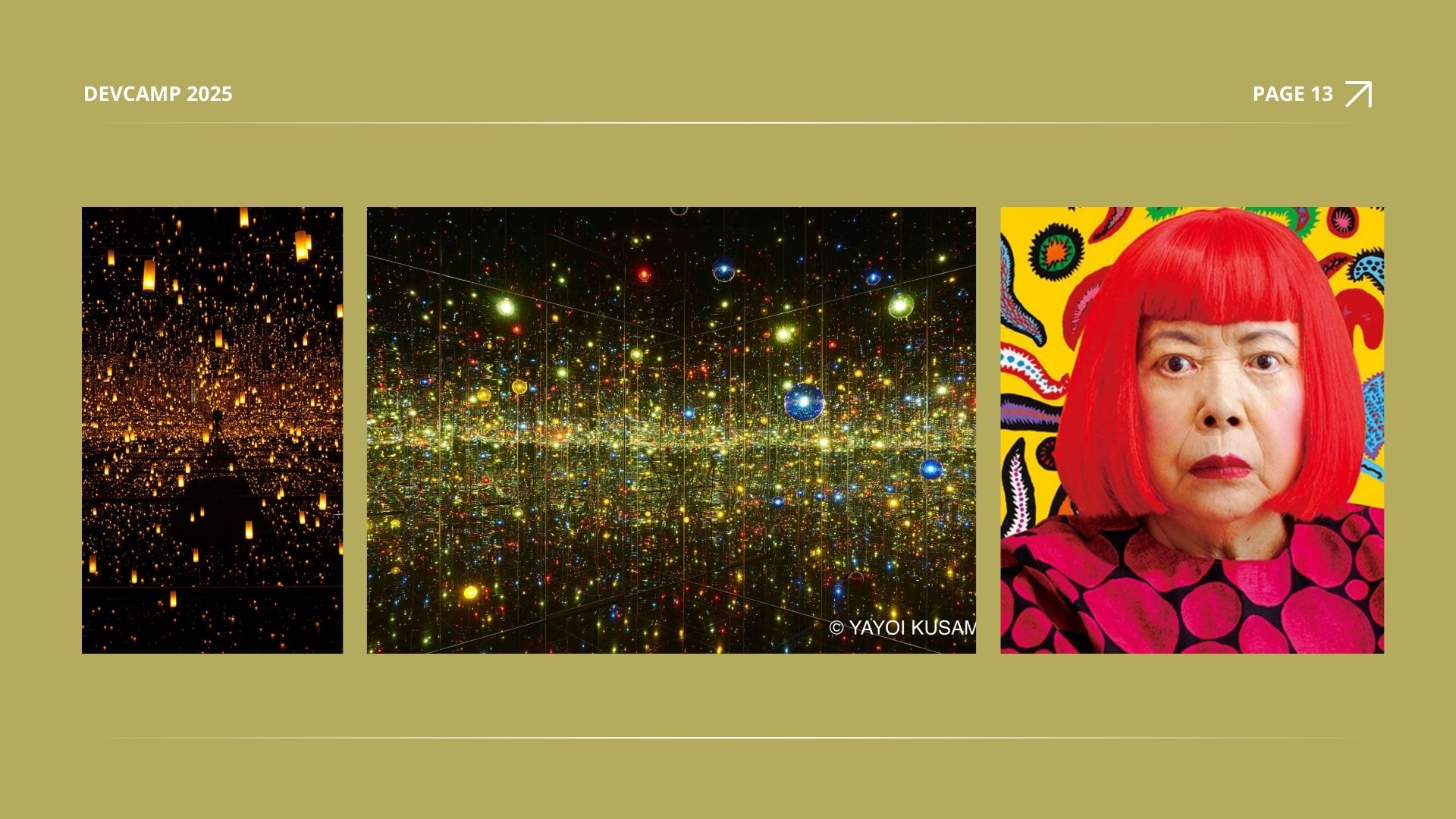

Then there’s Yayoi Kusama, whose endless polka dots and infinity mirrored rooms are maps of a mind. When visitors step into these spaces, they inhabit the claustrophobia and cosmic wonder of her neurodivergent reality.

An AI could generate images of flowers growing from spines or design infinite patterns. But it has never done what these people have done, and later turned those same visions into art that heals millions.

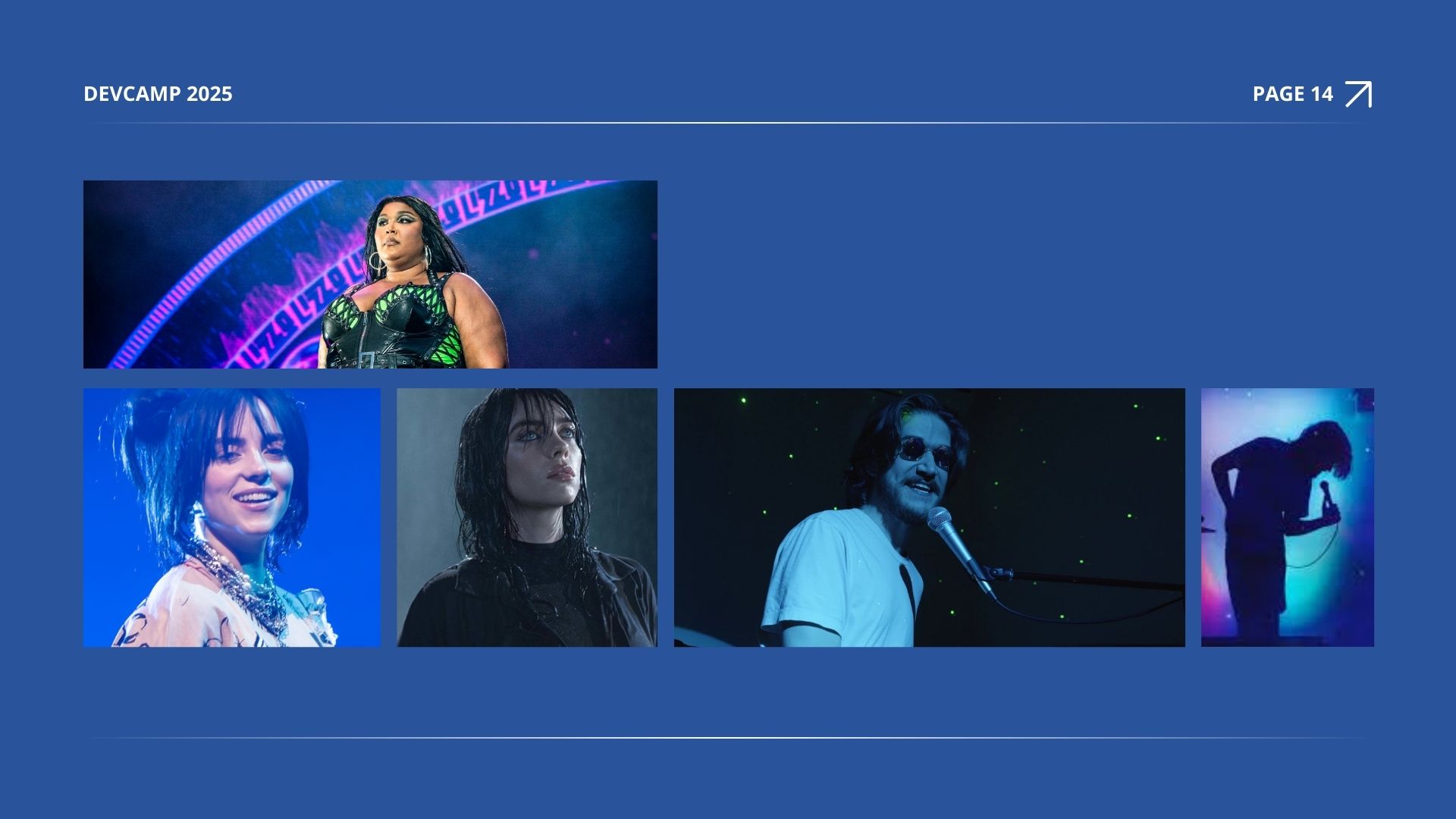

Meanwhile, Billie Eilish’s whispered vocals and intimate production style create an authenticity that resonates with millions. Lizzo’s celebration of her body and identity challenges perfectionist beauty standards while creating joyful, vulnerable music. Bo Burnham’s “Inside” special, created during the pandemic, includes mistakes, breakdowns, and moments of struggle with mental health.

Consider Janelle Monáe, whose work blends Afrofuturism, science fiction, and deeply personal storytelling in ways no algorithm would generate. Or visual artists like David Shrigley, whose deliberately crude drawings and absurdist humour cut through the noise of clean AI art.

What these creators share isn’t technical perfection—it’s a distinctive voice and perspective. They’re not trying to appeal to everyone.

While AI strives for consistency like a McDonald’s burger line, we humans connect through our beautiful messiness. Our voices crack with emotion. Our hands tremble slightly as we draw. These “flaws” are vessels for authenticity.

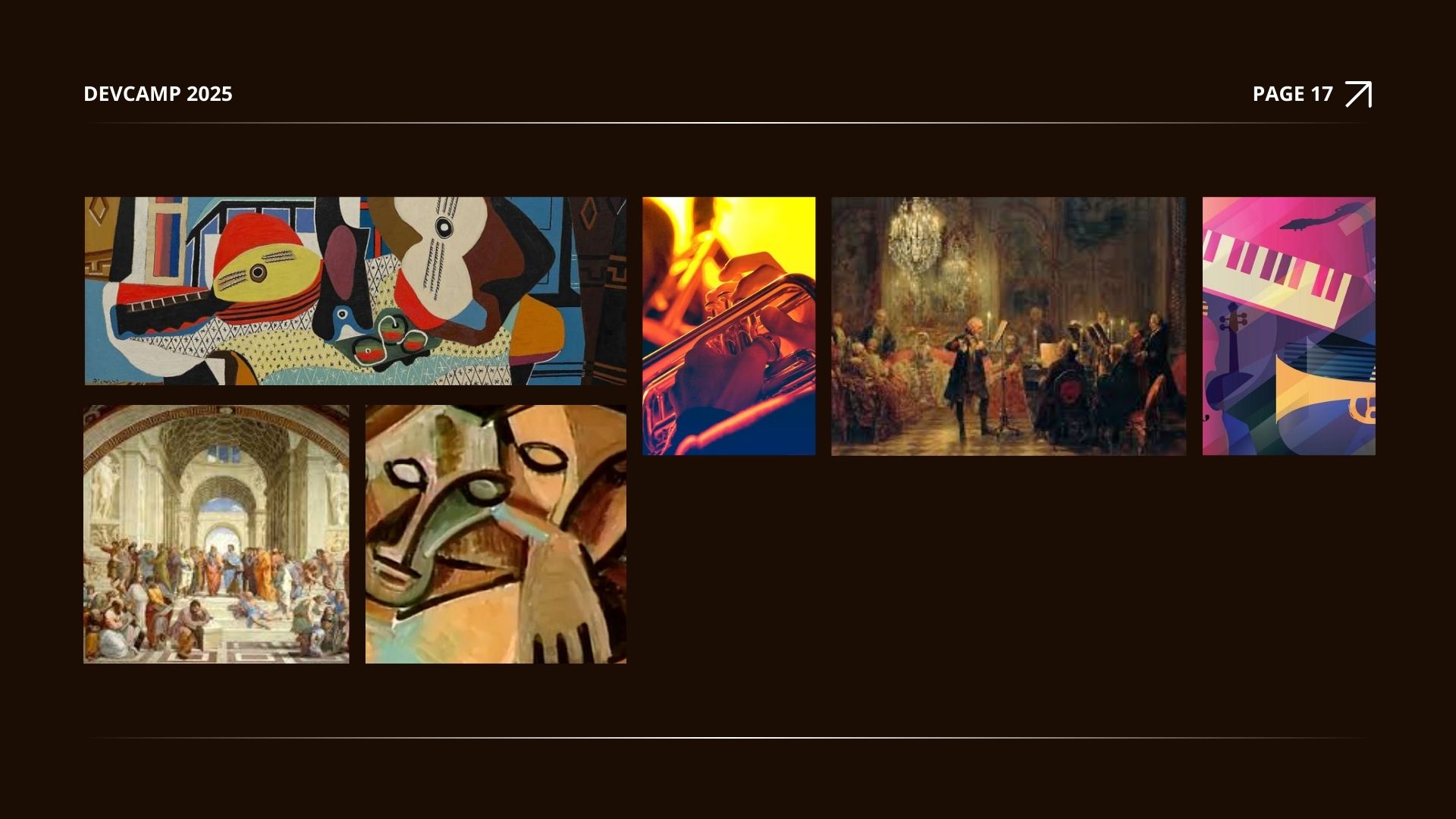

Would AI have invented cubism if trained only on Renaissance paintings? Would it have come up with jazz if it had only been fed classical music?

Paradigm shifts happen when humans break the rules deliberately, often because they’re bored, frustrated, or simply curious about what lies beyond convention.

AI can’t rebel against its training. It can’t wake up one morning and think, “I’m tired of creating in this style—what if I tried something completely different?” It doesn’t have those moments of inspiration while taking a shower or walking in nature. It doesn’t feel the urgency to express something that’s never been expressed before.

Art exists in conversation with culture, history, and shared human experiences. When artists reference cultural trauma, collective joy, or shared myths, they tap into a communal consciousness that gives their work depth and resonance. We recognise ourselves in powerful creative work. We see our struggles, our hopes, and our fears reflected back at us. We feel seen.

So yes, AI can create content that looks creative. But when we talk about creativity that matters—that moves us, changes us, connects us—that’s still beautifully human. As AI floods every channel with increasingly homogenised content, anything distinctive becomes more valuable, not less.

But AI does have weaknesses. It struggles with intentional absurdity, culturally specific nuance, humour that relies on shared human experiences, deliberate rule-breaking, and getting detailed. When AI goes wrong and makes a mistake, it does it differently than we do.

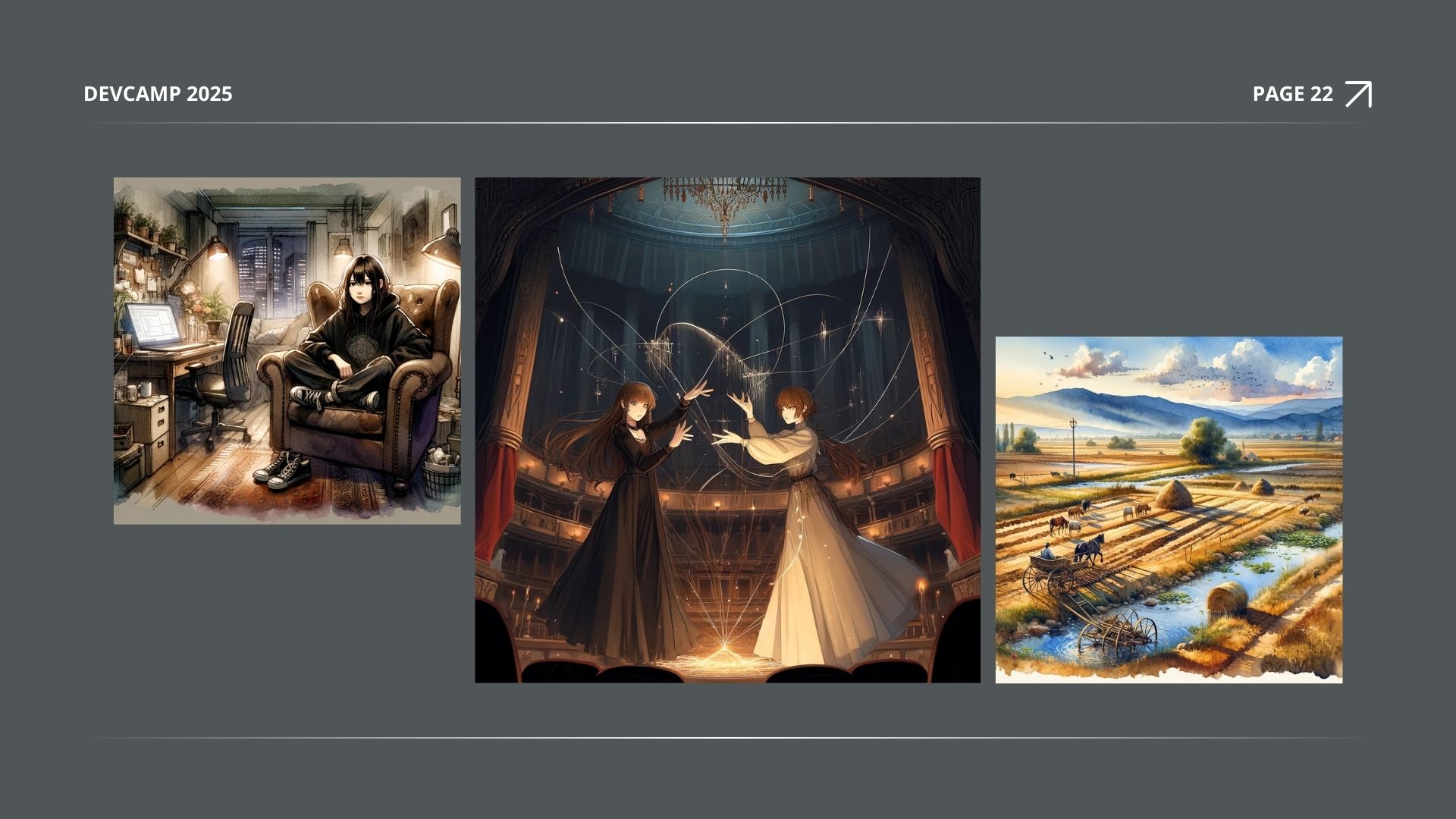

What’s happening to the wheels on the chariot? Why are there extra horses riding it? Why is the woman floating next to the chariot instead of on it?

Why is there a deer/rabbit creature with two heads and weird antlers?

Here I asked ChatGPT to take my shoes off because I don’t wear them indoors, and it simply placed an extra pair of shoes at my feet.

It failed to depict two women weaving the threads of fate coherently.

And I’m not sure what’s happening with those animals and the extra wagon in the third image.

Nevertheless, we’ve found ground for distinctively human creation if we can identify these weaknesses.

Human intuition includes our ability to read a room and adjust our message, our sense of what will resonate emotionally with other humans, and our feel for timing, for what’s culturally resonant in this exact moment.

Or, what if we leaned into the strangeness of the human-AI creative relationship? What if we deliberately played with the tensions and frictions that arise when human creativity meets machine learning?

Some interesting art being made today does exactly this—it doesn’t reject AI tools, but it doesn’t worship them either. It uses them as strange new instruments of creative expression.

Fashion designer Iris van Herpen incorporates AI-generated patterns and 3D printing into her designs, using algorithmic tools to achieve organic structures.

Oscar Sharp co-created “Sunspring,” a short film with an AI-written script, but brought his human directorial vision to interpret and film it in a way that highlighted both the AI’s creativity and its limitations.

But so many people lean on AI for creativity because it’s so hard to feel confident being creative. There’s something deeply vulnerable about creating—about putting your ideas out into the world and risking that they might be seen as boring, derivative, or just plain bad. The blank page, the empty canvas, the blinking cursor—they can feel like judgments waiting to happen.

AI offers a kind of creative safety net, generating ideas that feel “good enough” without requiring us to expose our own uncertain creative instincts.

Here’s what I’m learning: creativity isn’t about confidence—it’s about curiosity. And sometimes, the best way to bypass that creative paralysis is to give myself smaller, more manageable challenges.

One general approach that I’ve found helpful throughout my life, however, is constraint. At some point, I learnt that imposing limitations often sparks greater creativity than complete freedom. This paradox works because constraints force me to connect ideas I wouldn’t naturally combine.

Without boundaries, many of us gravitate toward familiar territory. Constraints act like roadblocks across these comfortable paths, pushing us to explore regions we’d otherwise avoid.

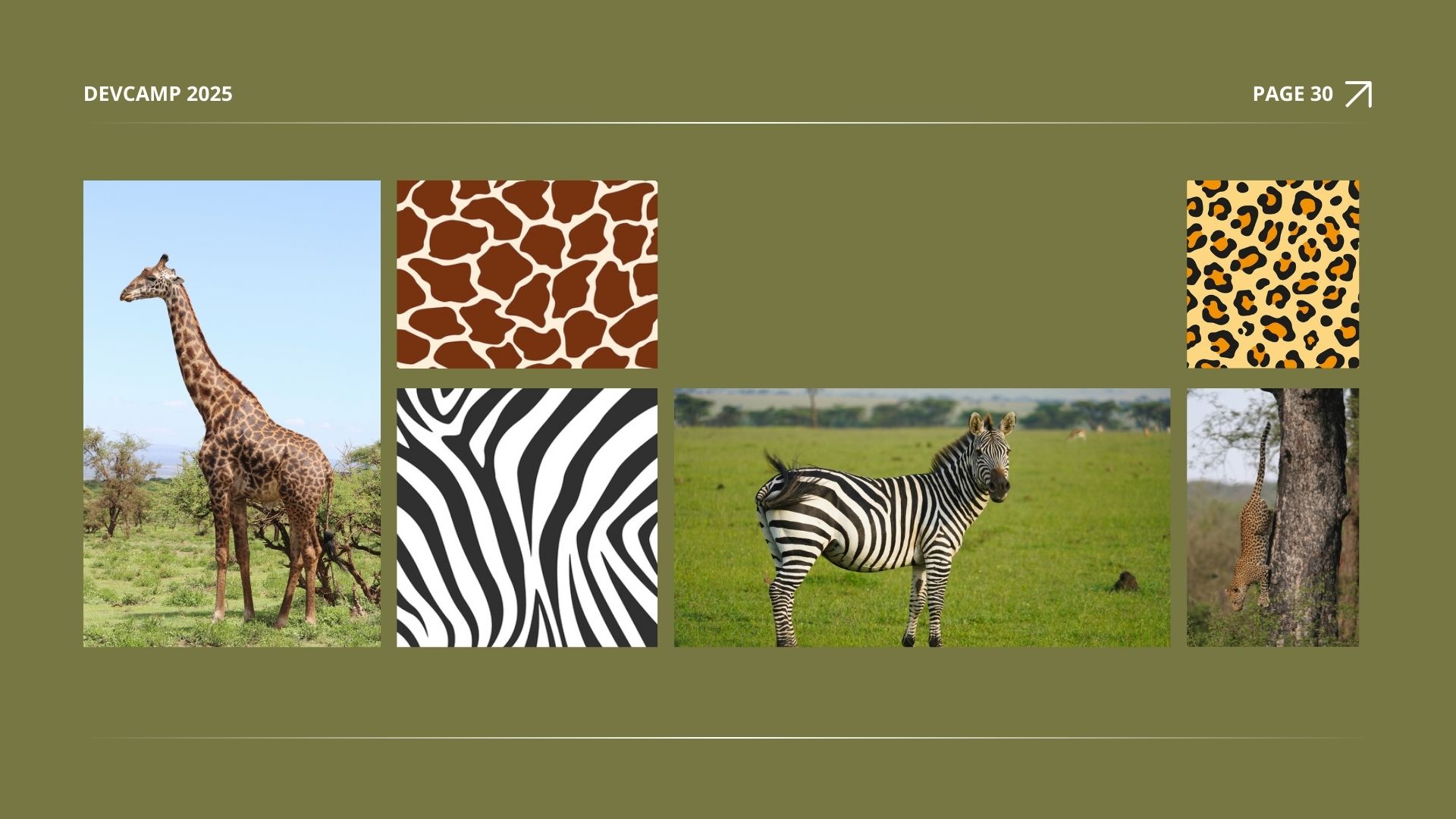

But it works differently for everyone. For example, during one of my university classes, we were asked to take these patterns here and create animals from them. This constraint led many people to create many simple animals. The giraffe pattern naturally drew many to creating giraffes; the same was true for the zebra and leopard. Also, the triangle constraint led many to use simple triangular shapes for each animal’s body part.

But this really worked for me. I tested the boundaries. And in the end, I was the only one in the class to come up with...

This. I used all three patterns, more triangles than necessary, and tinted them to become colours more suited to my goals. I stretched the definition of “animal” by creating Pokémon.

Constraints really work for me. Something about my brain draws me to the edges of what I’m allowed to do.

This is like creating with deliberate restrictions—use only certain colours or fabrics, write without using a common letter or from a unique perspective, and compose music in an unusual time signature. The result doesn’t have to be unique—the constraint simply must force you to think.

Because while people say, “think outside the box,” thinking outside the box is hard. Even a sandbox is technically a creative restriction, but—similar to the patterns—it’s hard to break our minds away from creating a sand castle. Many of the most impressive sand sculptures on the beach are simply larger, more detailed sand castles. Followed closely by mermaids. Because thinking “outside the box” is so challenging.

But here’s the problem I realised. The phrase is simple, making the concept seem simple, but trying to think of something no one else has done before is not simple. The times that people achieve such things, their names are often recorded in human history, and they’re considered great minds.

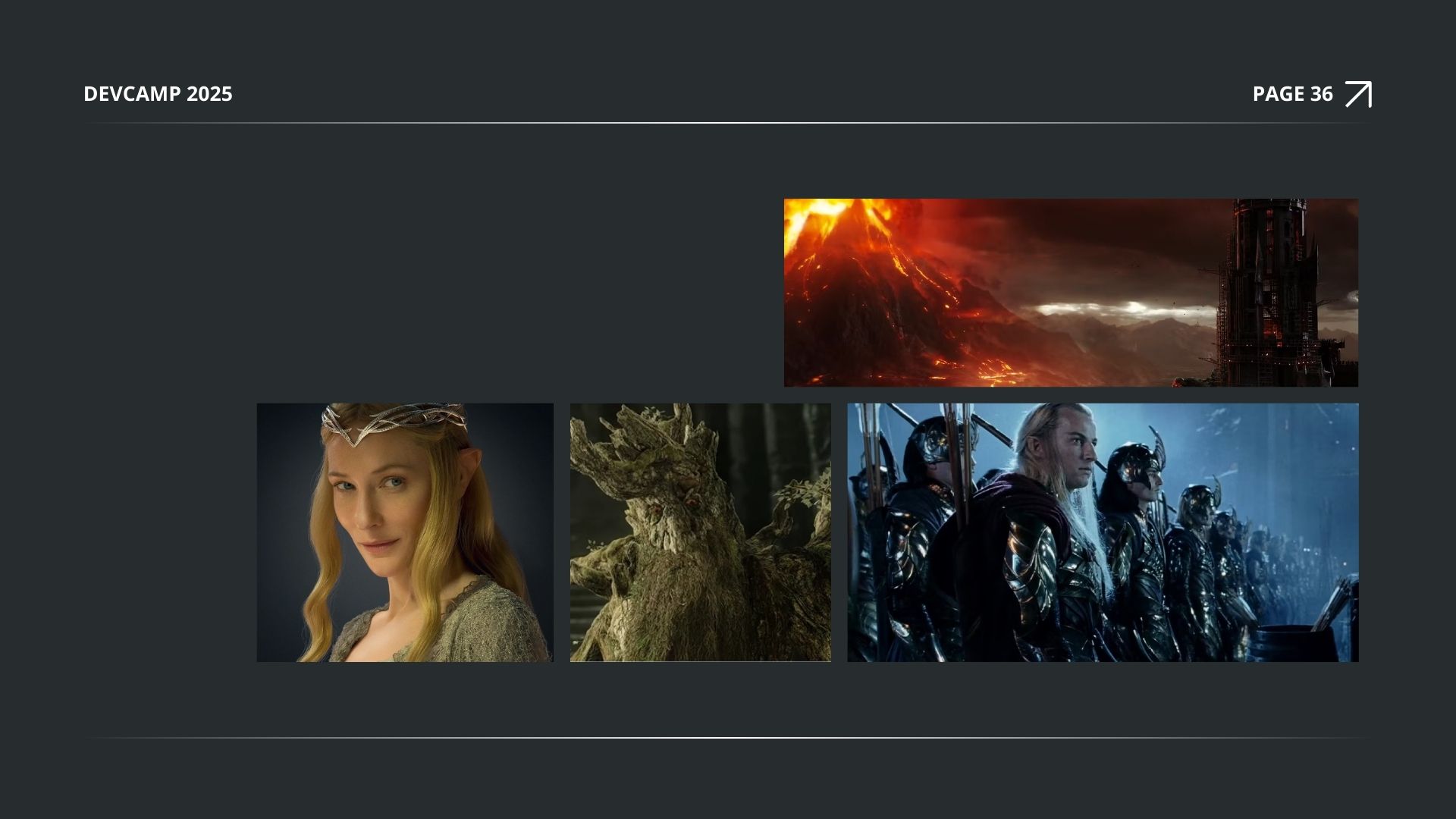

But even greatness is not “great” all of the time. Let’s consider JRR Tolkien, the author of The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings, whose work has become a legacy that has spawned many other works. One thing he’s well-known for is the depth of his world’s languages. He wrote a language for a race of people, full of history and lore. Then he named a mountain Mount Doom. He called a beautiful woman Galadriel, which means “maiden crowned with a radiant garland” or “maiden crowned with a gleaming crown” in one of his languages. However, he also named a character Treebeard because he’s a tree with a beard.

This is actually how many things in the world are named, too. My Chinese surname means “river”, and my English surname means “brook”, as in “stream,” or, if you prefer, the shoe brand. My partner lived in a suburb that translates to “death valley” and grew up next to a “grandma’s mountain.” It’s reassuring to think that not everything we do has to be the most fantastic thing of its kind, and that many things are more mundane and “average” than they seem. It’s mostly a matter of perspective.

Which brings me to another technique I’ve tried working with. Deliberate defamiliarisation—taking something familiar and making it strange. The Surrealists played games like “Exquisite Corpse” to break from conventional associations. Edwin Abbott wrote a book about a society of 2D shapes that incidentally reveals a lot about how we live our 3D human-shaped lives. I could try describing everyday objects as if I’m seeing them for the first time, or combining elements from wildly different contexts.

But how does any of this apply to software engineering? Our field moves too fast for AI training data to keep up. New frameworks emerge, best practices evolve, and security standards shift while AI models remain frozen in their training snapshots. LLMs frequently suggest deprecated methods, miss crucial updates, and hallucinate content that never existed.

We become the bridge between AI’s statistical knowledge and what’s actually happening in our field. We’re creative interpreters, translating between what AI thinks coding looks like and what coding actually requires right now.

Even more importantly, front-end development has always been creative. Every intuitive interface, every interaction that feels effortless, every design that somehow anticipates what users want—these emerge from the same creative spark. We don’t just implement accessibility guidelines; we imagine how a person navigating with a screen reader experiences their interface. We understand that someone with limited motor control needs different interaction patterns than someone using a mouse. We recognise that cognitive accessibility is about designing with genuine empathy for how different minds process information.

This is knowledge that AI won’t replicate. We recognise the anxiety of a form that doesn’t clearly communicate what went wrong. We feel the satisfaction of an animation that guides rather than distracts.

When we design a colour palette, we’re not just picking aesthetically pleasing combinations—we’re considering how someone with deuteranopia will distinguish between states, how those colours will appear under fluorescent office lighting, and how they’ll translate across different devices and contexts.

AI can generate component libraries and suggest colour schemes more interesting than TailwindCSS pretty easily. Still, it can’t observe a user’s confused expression during testing, feel the frustration of a poorly designed checkout flow, or understand why a particular interaction pattern makes someone feel excluded or empowered.

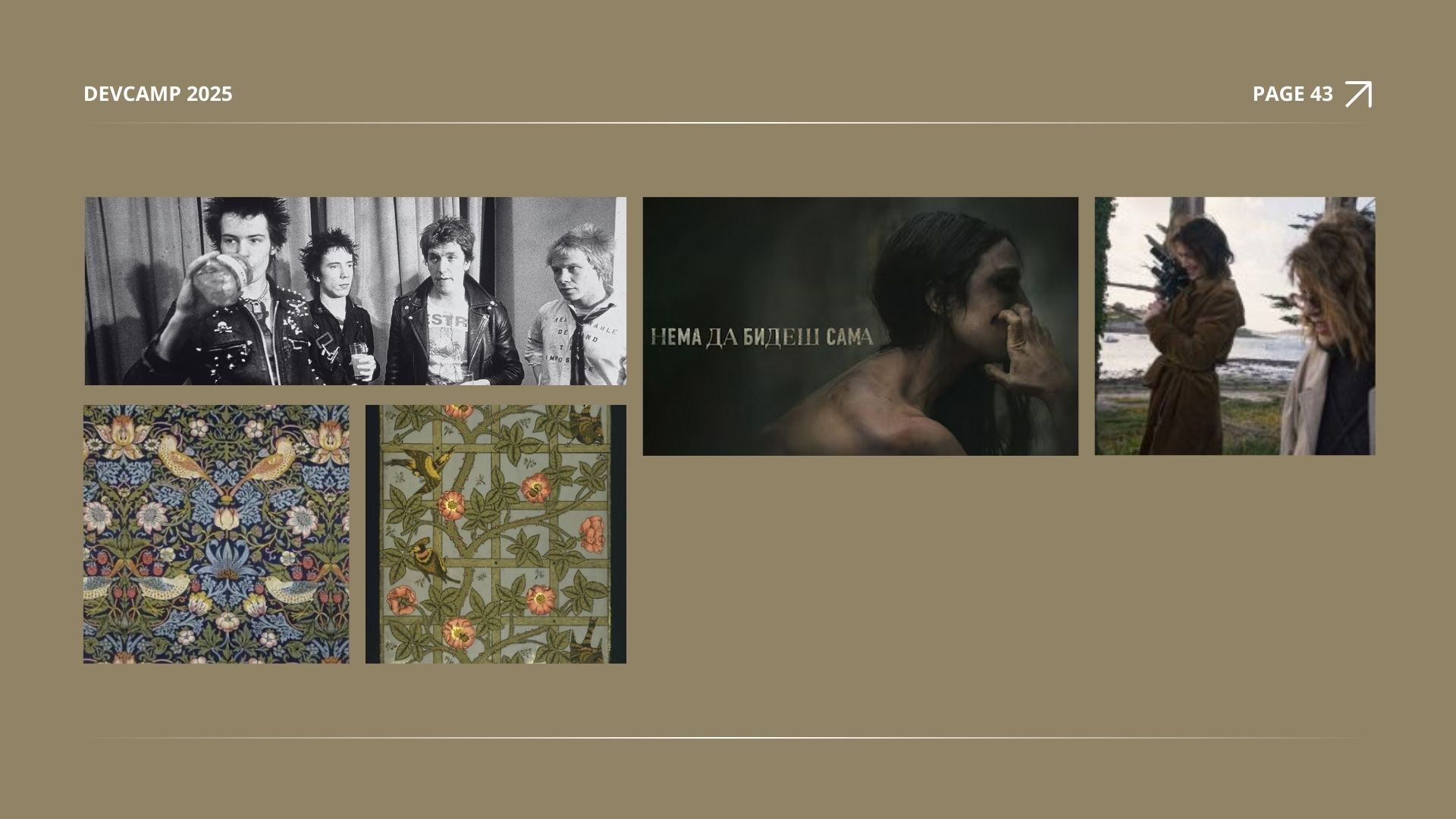

So, while we’ve arrived at yet another pivotal moment in creative history, it’s just another in a long stream of never-ending pivotal moments. Throughout history, creative revolutions have often emerged in response to periods of standardisation and mass production. The Arts and Crafts movement arose in reaction to industrial manufacturing. Punk rock exploded as a response to overproduced stadium rock. Indie filmmaking flourished as an alternative to formulaic Hollywood blockbusters.

But speaking of mass production, I think the real threat isn’t that AI will replace human creativity. If AI allows us to generate designs in minutes instead of hours, clients will expect turnarounds in minutes instead of hours. If we can prototype interfaces twice as fast, project timelines will shrink accordingly. We will be inheriting new productivity expectations that could fundamentally change how we work and what we’re able to create.

This creates a paradox: the very tools that could enhance our ability to get things done might trap us in cycles of faster, cheaper, more—leaving even less time for the deep thinking, iteration, and genuine innovation that distinguishes human creativity from algorithmic output.

I think recognising this pattern is the first step to resisting it. When we understand that our most valuable creative contributions require time, space, and deliberate inefficiency—the luxury of getting lost in a problem, of pursuing dead ends and failures that lead to unexpected discoveries and skill acquisition—we can begin to defend those spaces.

But nevertheless, how we navigate those productivity pressures deserves its own deep dive.

First, we need to remember what’s worth protecting about human creativity in the first place.

So, for now, it’s your turn. Your strange, human, unpredictable, creative voice are qualities that make your work distinctively yours... These are precisely what cannot be algorithmically generated.

Don’t try to compete with AI on its terms—speed, volume, or technical perfection. No, these things didn’t make us stand out before AI and won’t now. Lean into the aspects of creativity that machines cannot touch—meaning, intention, emotion, cultural context, and moral purpose.

In the end, AI hasn’t ended human creativity. It’s clarified what was always most valuable about it—the irreplaceable human spark that makes something truly you.

Do androids dream of original ideas? No.

But you do.

Take this as your permission slip to let your unique and weird run free.